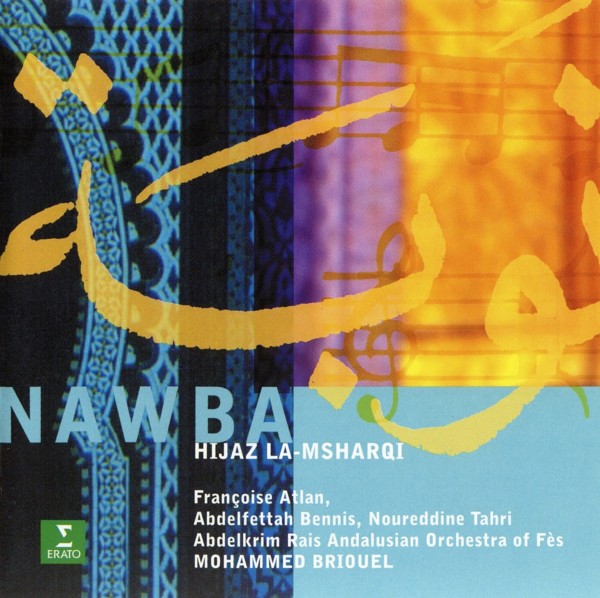

ERATO 3984-25499-2

1999

1. Mizan Bacit [20:14]

2. Mizan Btayhi & Ddarj [32:52]

François Atlan, soprano

Abdelfettah Bennis, tenor

Noureddine Tahri, tenor

Abdelkrim Rais Andalusian Orchestra of Fès

(ORQUESTA ANDALUSÍ DE FEZ)

Mohammed Briouel

Mohammed Arabi, violín

Mohammed Briouel, Dris Bennis, Mustapha Amri, viola

Ahmed Trachene, cello

Abdelhay Bennani, rebab

Abdemahim Otmani, Rachid Lebbar, Ahmed Chiki, ud

Aziz Alami, tar

Abdesslam Amri, darbuka

Recorded in the Mnehbi Palace, in the heart of the Medina at Fès (Morocco)

Producer: Ysabelle Van Wersch-Cot

Sound engineer: Jacques Dolt

Assistant: Didier Jean

Editing: Ysabelle Van Wersch-Cot

Recording: October 18,1998

Recorded using "Audioline Conditionner"

by Hologram', Ch-2400 Le Locle

Cover & Back cover: Royal Palace of Fes (C) HOA.QUI

Design: Erato Disques

Ⓟ & © Erato Disques, S.A, Paris, France 1999

3984-25499-2

Erato web site: www.erato.com

FRANÇOISE ATLAN AND THE ART OF THE MOROCCAN NAWBA

Christian Poché

Here,

we have a most unusual performance: combining the voice of Françoise

Atlan with a vocal art which has been passed down by men's voices is

something as unusual as it is original. The arrival of this new vocal

timbre into the aesthetics of the nawba overturns all the accepted

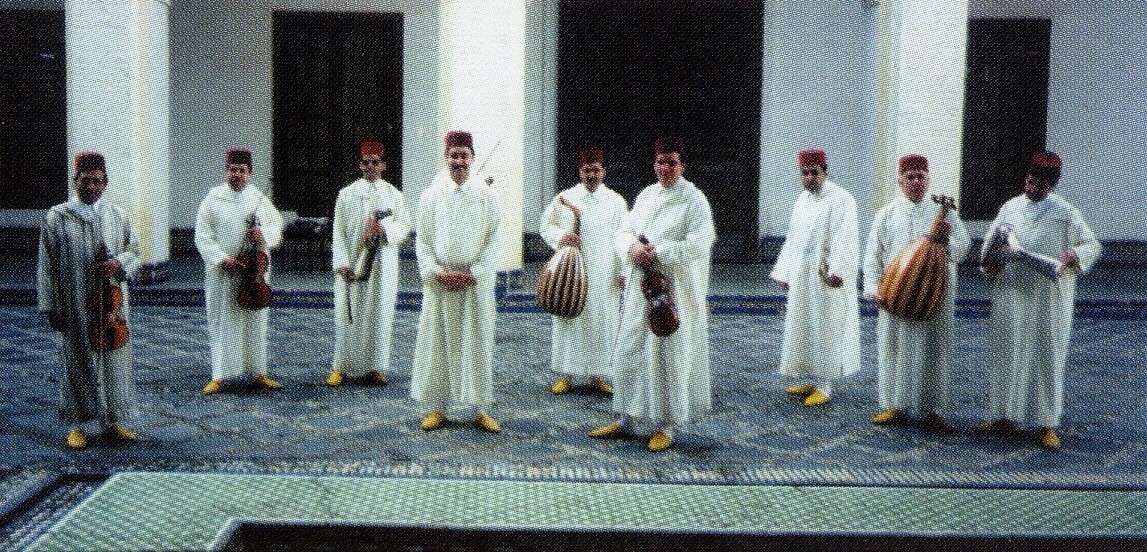

rules. The performers, led by Mohammed Briouel, conductor of the

Abdelkrim Rais Orchestra (it was Abdelkrim Rais who founded this

orchestra and who was its guide and mentor for over half-a-century;

today, it bears his name and it has become the Fès Orchestra for the

performance of Andalusian-Maghrebian music), had the idea of entrusting

Françoise Atlan with a solo role in order to acknowledge her talent more

suitably. This gives a totally different configuration to the nawba,

one which can be described in the single word, "responsorial". The

chorus of instrumentalists constantly replies to the female voice, for

in the Arab-Andalusian art as it has survived in Morocco, the

instrumentalists double up as singers. Nevertheless, this manner of

singing in reply is not the usual custom in the Moroccan tradition and

even less so in Fès. It is true that in the rare written authorities

that have come down to us on this sophisticated art which is essentially

an oral tradition, there is no mention at all of the distribution of

the vocal parts. Everything here is a matter of conjecture. Moroccan

ensembles as a general rule sing in unison, or at the octave or even in

antiphony. A responsorial system is one unknown to them. It applies more

to the performance of the Algerian nawba, particularly in the closing

section. But responsorial and antiphonal interpretations, and their

variants, are universal forms and they do not conflict in any way with

the original aspects of the art.

But what is it all about? It is

an art born in the country of al-Andalus and handed down from master to

pupil. It took refuge in a few towns in North Africa where it was

constantly developed and enriched in a profusion of sung poems. The

pieces are extraordinarily long, so much so that Moroccan nawbas are no

longer performed in their entirety - performers limit themselves to

choosing a few extracts.

"Nawba" is a term which throughout its

history has been endowed with various meanings. It appears in the

Baghdad of the Abbasid Caliphate, but at that epoch towards the end of

the ninth century, it had quite another meaning: it applied to what was

performed while waiting one's turn in order to go to the palace to play

and sing music before the Caliph. There was a nawba for Thursday,

another for Friday and so on. Once it had travelled towards the west of

al-Andalus, where the frontiers were always subject to change, it took

on an entirely different style: it was a question of performing a

succession of pieces which became ever faster. In essence, these pieces

made up a sung musical suite sustained by instruments amongst which the

lute (ud), the boat-shaped bowed vielle (rebab) and of course a

membranophonic percussion instrument were the principle support and

without which the art could not have been expressed. By announcing the

rhythm, the percussion instrument guaranteed that the message of the

sung text would be properly transmitted. The instrumentation took on

particular importance, and this is reflected in the fact that the word

"ala", by which the art is traditionally known in Morocco, means quite

simply "instrumental".

Thanks to the genius of a compiler named

al-Hâ'ik, who hailed from Tétouan and is thought to have lived in the

eighteenth century, Moroccans now have access to the texts of the poems

of the nawba. al-Hâ'ik assembled them in a manuscript which was included

in an ensemble bearing the title of Kunnâsh, which means a collection

of poems. al-Hâ'ik did not know them all. However, twentieth-century

musicologists have traced other compilers, including al-Bucsami who had

hitherto been neglected. al-Bucsami lived towards the end of the

sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth centuries and he, too,

played a leading role in securing knowledge of this heritage.

Nevertheless,

the Moroccans, who are the heirs of the nawba, recognize al-Hâ'ik as

their father and master. It was he who unearthed the existence of eleven

nawbas and codified them. It was he who determined the speeds by

discovering the corresponding musical modes. Arab-Andalusian music as it

is practised in Morocco today does not make use of micro-intervals. As a

general rule, performers from elsewhere do not take easily to it. This

is not the case, however, of Françoise Atlan, who was also trained in

Judeo-Spanish music, and she had no difficulty in adapting to the music,

to her great delight. She also leads the movement (mizân) called basit

(simple) of the nawba Hijâz al-mashriqî with great success, albeit with a

shift in meaning. There is intimate and spontaneous joy in this music

and the listener is also absorbed by the atmosphere of piety which it

distils. This is the usual feeling aroused by the nawba as it is played

today in Tlemcen (Algeria), although not in the sister land of Morocco.

The

nawba Hijâz al-mashriqî, pronounced in dialect lmsharqi, is the ninth

in the order attributed by al-Hâ'ik. The musical scale is based on the

mode of D with the F being raised to F sharp. Although it is a case here

of the heptatonic scale, the nawba traditionally develops around a

narrow range. For the purposes of the present recording, three of the

five opening movements have been selected. There are two nawbas in Hijâz

in the Moroccan tradition: the one known as al-kabîr (the great Hedjaz)

and other called al-mashriqî (Hedjaz from the East). These two modes

have the same scale but they differ in the size of the pivotal steps:

tonic, fifth and octave in the case of the Hijâz al-mashriqi, and tonic,

fourth and fifth in that of the Hijâz al-kabîr.

Noubas are

traditionally performed with a constant increase of tempo. The poems are

for the main part in dialect and develop the three main themes of the

genre: love personified by absence, and waiting which generates passion.

As for nature, it procures an almost drunken state and is often a call

to the divine.

Translation: John Sigdwick

These

poems "HIJAZ LA-MSHARQI" feature in the 9th Nawba; they were produced in

Andalusia in Spain and they continue to be called La-Msharqi on account

of their oriental origin.

The poems sing of the beauty and splendour

of the beloved, going so far as to describe all the various parts of

her body, including every one of them, even those that are the most

intimate and concealed.

They begin with the face, one that is endowed

with features of unheard-of beauty whose charm and brilliance propagate

all sorts of bewitchment and enchantment which never cease to seduce

and fascinate the heart of the poet.

The poet also sings of the

blackness of the beloved's eyes; he sings, too, of her eyelashes and her

eyebrows, comparing them with a host of heavenly delights.

In its

turn, it is the mouth which dazzles, both by its shape and by the smile

which it portrays; in addition, there are the beautiful words which flow

through it, intoned by a most beautiful voice.

The emotion is such that the eternal gaze that is cast upon it could never suffice to quench the thirst to admire it.

The

poet has the impression that sparks fly out from the cheeks of the

beloved. But what exactly are these sparks? They are ones which drive

you to believe that you are in the presence of fairies or of angels

which stretch out their hands to bear you far off, very far off to a

distant and wonderful world where everything is fine and perfect.

There

is a mole on the beloved's cheek, and this in turn helps to bring out

the whiteness of her skin. This mole attracts your attention, whatever

the state of lethargy you might happen to be in. You have the impression

that through this tiny dark dot you can see a host of things that you

endeavour to recognize and identify, but which fly away, leaving room

for others in an infinite cycle.

In this semaâ (group of lines), the

poet moves from a description of the beauty of his beloved's features to

the expression of his feelings for her, saying that everything in this

world will come to an end, everything, that is, save his love for her.

The

poet even goes so far as to swear by all that is most dear to him and

begins by quoting one after the other the forehead, the eyes, the mole

etc. in a manner whereby the words themselves take on a musical

atmosphere.

Mohammed Briouel - Translation: John Sigdwick