medieval.org

Raum Klang 9901

Raum Klang "Souvenir" 59901

1999

medieval.org

Raum Klang 9901

Raum Klang "Souvenir" 59901

1999

1. Waedamah [4:14]

Text: final line of a Piyyut of unknown origin

Music: Obadiah (~ 1100)

“And I wept and I spoke under the gates and the community taught me.”

This

piece was written by Obadiah. Born in Oppido, Lucano (Italy) as

Iohannes, he was the son of a Norman aristocrat named Dreux. Shortly

after having taken the vows to become a catholic priest, he converted to

Judaism (~ 1102), as a consequence of a dream he experienced. His

varied life took him on travels through Constantinople, Baghdad and

Aleppo to North Palestine and finally via Tyre to Egypt, where he then

settled in Fostat. During these years he studied intensively and became

renowned as a scholar. All his works, including his autobiography, were

found in the Cairo Geniza. (The Hebrew word “geniza” refers to a place set aside for the storage of ritually inappropriate documents.)

2. Shir ha—Shirim [3:35]

Text: Song of Songs III/1

Music: Improvisation

“By night on my bed I sought him whom my soul loveth: I sought him but/found him not”

3. Ki mi—Zion teze Torah [1:01]

Text: Isaiah II/3

Music: Improvisation

“For the Torah emerges from Zion and God's word from Jerusalem.”

All

the improvisations recorded here are based on the torah tropes noted

down by Johannes Reuchlin in the sixteenth century. These tropes cannot

carry meaning as such like a word. The idea is for them to subdivide a

long sentence into smaller logical units and their function is therefore

to serve both the dramaturgy and syntax. In principle, even these

melodic cells, depicted graphically by, for example, a dot or a loop,

can be exchanged.(As such, they differ from neumes, which try to pin

down a musical event.) The flexibility of the tropes therefore explains

regional differences in their execution and also allows entirely new

melodies to be created. However, the presence of an underlying tonal,

functional structure is prerequisite and is usually provided by the

interval of a fourth or a fifth, a factor that again links the tradition

with that of Gregorian chant.

4. Mi al Har Horev [4:34]

Text: Piyyut by “Amr”

Music: Obadiah

“Who was as strong and sure in his belief as was Moses on Mount Horeb?”

The

author of this piyyut was “Amr”, according to an acrostic using these

letters in the text. The piyyut was intended for use during the two

holidays Shawuot and Simhat Torah: both are festivals which celebrate,

at different moments of the Jewish calendar, the reception of the Torah

at Mount Horeb. The people, and thus every individual, receives the

Torah, which is therefore not solely transmitted through Moses. However,

according to the text, nobody can compare himself to Moses. There are

neumes for this piyyut, which were written down by Obadiah and are read,

like the text, from right to left.

5. Adonai ma Adam [4:40]

Text: Shlomo Ibn Gabirol (1028-1058)

Music: anonymous

“What is man, Oh Lord? Were not he from flesh and blood, his days would pass like shadows and would go unnoticed.”

6. Barukh ha—Gever [2:47]

Text: Jeremiah, Proverbs, Job

Music: Obadiah

“Blessed is the man who trusts in God.”

7. Kevarim [3:54]

Text: Moses Ibn Ezra (1055-1139)

Music: anonymous

“Graves

from ages long past and in them lies a people as old as the world and

no Hatred and no Envy in them and no Love and no Hatred for the other.

And it is impossible to distinguish the servant from the master.”

Ibn

Ezra, born in Granada, was one of the most prolific poets of his time.

He held an important position in Granada and witnessed the assault by

the Almoravids in 1090, through which the entire Jewish community of the

town was destroyed. After the assault, he fled to the Christian part of

Spain, an area in which he then remained but always felt a stranger.

8. Shir ha—Shirim [3:18]

Text: Song of Songs III/4

Music: Improvisation

“Scarcely had I passed them when I found him whom my soul loveth.”

9. Le mi Anuss [3:08]

Text: Isaac Ha-Gorni (13th century)

Music: Contrafactum to “Ja nuns hons pris” ascribed to Richard the Lionheart (1157-1199)

“Woe

betide him who is in despair and cannot find support as, alas, is poor

Gorni who receives only in mockery and deprecation who is without money

and support. Perhaps my fate is my heritage and my wealth and misery my

pillar.”

Isaac

ben Abraham Ha-Gorni from Aire in the South West of France chose to

express himself in Hebrew. According to contemporary witnesses, Gorni

never settled down and was eternally dependent upon masters. Throughout

his journeys to all the important centres of southern France in the 13th

century, he frequently complained about the shallowness of the culture

and the narrow-mindedness of the inhabitants. Unsurprisingly, this often

caused conflict with his contemporaries and fellow poets, like Abraham

Bedersi of Perpignan who replied with poetic mockery. Gorni's literary

testament is full of sarcasm and bitterness and is one of the most

unusual examples of medieval poetry.

10. Quant voi les oisiaus esjoir [3:03]

Text: Robert de Blois (13th century)

Music: Contrafactum to “Onque del beverage ne bai” by Chrétien de Troyes (fl. ~ 1160-1190)

“When I hear the birds rejoicing over the sweetness of the season, I then sing their song to numb my pain.”

Trouvere song

11. [6:42]

Merci douce Dame

Text: Mathieu le Juif (13th century)

Music: Contrafactum to “Bien doit chanter”, anonymous (13th century)

“I

beg thee, show mercy with me, my, sweet Lady, for with thee I have not

brought guilt upon myself. For thee have I forsaken my covenant and my

belief in God against the will of my friends, and thou art making a fool

out of me. Thou hast betrayed me, as they have taught thee.”

Et s'autrement ne puis

Text: ibid

Music: Contrafactum to “Mon caret mi”, anonymous (13th century)

“And

if I cannot gain thy love, then may God make her so old and shrivelled

that the whole world, other than I, hates her. And then I would know

whether she would become a slave to me.”

12. Swer adellîchen tuot [1:51]

Text: Süskind von Trimberg (~ 1200-1250)

Music: Contrafactum to “Aspis ein wurm geheizen is”,

ascribed to Konrad von Würzburg (1220/30-1287)

“Whoever

acts in decency I wish to call noble. One can no more recognise

nobility from recorded lineage, than the rose by the thorn. And where

men violate virtue's duties, there the robes of nobility fall into mere

pieces. Yet he who is upright and does his duty, he who needs no name

but honours virtue, him I call noble, even were he not of noble origin.”

Süskind

von Trimberg, a German minstrel of Franconian origin, is the only

German medieval poet known to have devoted his attention to Jewish

subjects. Hardly anything is known about his life.

13. [4:37]

Küng Herre, hochgelopter Got

Text: Süskind von Trimberg

Music: Contrafactum to “Sit man daz bone bi den guoten”,

by Rumslant (fl. 1273-1286)

“King,

Lord, highly praised God, all power rests in you. You lighten up with

the day and darken with the night. You grant us joy and rest. In you all

beauty is revealed and all you create will remain for eternity”

Ir manes krone

Text and Music: ibid.

“A

virtuous wife is a man's crown. What she possesses honours him: purity

in body and soul. Fortunate is he whom she assists and who spends year

after year in joy with her! To her highest praise have/made this song.”

14. Gedenke nieman kann erwern [2:37]

Text: Süskind von Trimberg

Music: Contrafactum to “Nu merke ho un edle man”,

by Friedrich von Sonnenburg († before 1287)

“Thoughts

are refused neither the foolish nor the wise. They are free to move

where they will, no matter whom they are meant for. Nothing can keep

them, neither stone, nor steel, nor iron. Thoughts are the possession of

man, as are heart and mind, no matter whether they then ripen into

action. One senses them, but cannot grasp them.”

15. Re'e Shemesh [2:00]

Text: Shlomo Ibn Gabirol (1020-1058)

Music: traditional sephardic

“See

the sun, how red it is when night falls, as if immersed in the purple

of a worm. You spread out towards North and South, and the wind of the

sea you cover with purple. And the earth, she is bare and naked. She

rests under the shadow of night, seeking shelter. The clouds darken in

deep grief over dear Yekutiel.”

16. Shir ha-Shirim [2:06]

Text: Song of Songs V/6,7

Music: Improvisation

“My

soul was in terror because he had turned away. I searched for him but I

found him not. I cried out for him but he gave no answer. The guards

who walk about the city found me and beat me until I was sore.”

17. [6:09]

Ir me quiero a Yerushalayim /

Ir me queria yo por este caminico

Text and Music: sephardic

“I

want to leave, mother, I want to go to Jerusalem. Night falls and yet

the dawn is upon us. Jerusalem, mother, which I see before me, grants me

light, like the waxing moon. In the holy temple is a seven-armed

menorah, which illuminates the world. In the holy temple three doves

fly. They converse with the Shekhina face to face.”

Libi be'Misrakh

Text: Jehuda HaLevi (1080-1145)

“My

heart is in the East, yet I am on the other side of the West. How may I

taste it, the nourishment, how may I value it? How shall I fulfil all

my oaths, my commandments, whilst Zion is caught in the ropes of Edom

and I myself am chained to the West? With such ease would I leave

prosperous Spain behind, for so dear is the sight of the extinguished

ashes of the Holy of Holies.”

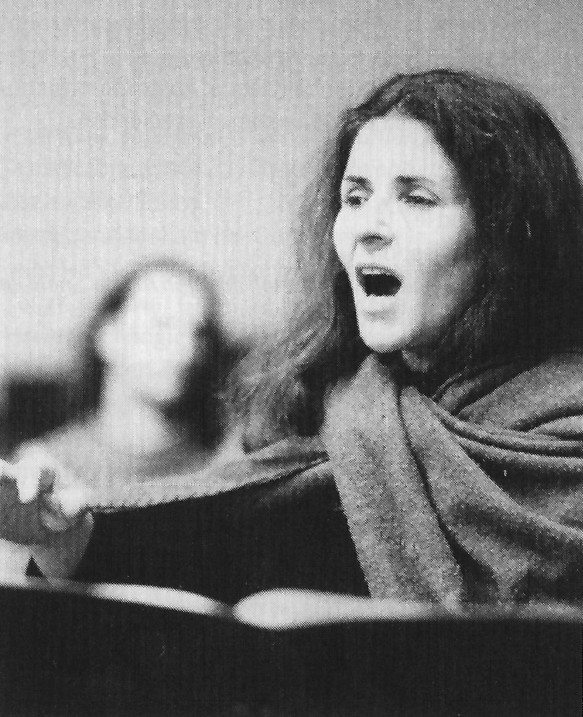

Jalda Rebling — Gesang

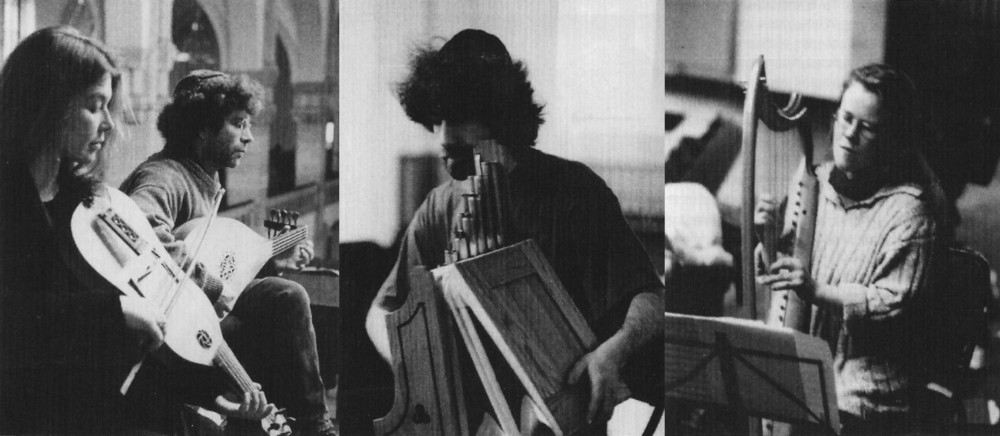

Hans-Werner Apel und Stefan Maass — Laute

Susanne Ansorg — Fidel

Sabine Heller— Harfe

Veit Heller — Portativ

Michael Metzler — Percussion

Translation: Jessica Marshall

Translation: Jessica Marshall

All texts in Hebrew, French and Middle High German can be found at the following internet address: www.raumklang.de

Wir danken der Synagogengemeinde Rykestraße und der

Jüdischen Gemeinde zu Berlin, daß sie diese Aufnahme

ermöglichten.

Wir bedanken uns bei Dr. Hanna Liss für ihre umfangreichen Recherchen.

Wir danken Prof. Karl E. Grözinger für seinen Rat.

Und wir danken Prof. Henning Schroeder für seine Beratung.

Die Aufnahmen fanden vom 2.-5. Februar 1999 in der Synagoge Rykestraße/Berlin Prenzlauer Berg statt.

Tonaufnahme und Schnitt: Sebastian Pank

Gestaltung/Satz: KOCMOC.NET Kathleen Rothe

Redaktion: Susanne Ansorg

Musikerfotografien: Silke Helmerdig

Alle Abbildungen stammen aus: L' art juif, Éditions Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris 1995.

Titelseite: Titelblatt des Gebetes Kol Nidre. Ritualbuch, Bodenseeraum, um 1320. (34,5 x 24,5 cm)

RKs 59901

© und ℗ Raumklang 1999

European Jewry

Whether or

not the names Mathieu le Juif and Süskind von Trimberg actually stand

for historically proven figures, their poetry mirrors the state of mind

of specific parts of European Jewry in the Middle Ages.

The term

"Middle Ages" covers a diverse period, which encompasses an equally

diverse society. This society had to reorientate itself as "Europe"

after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Polycentrism replaced central

administration, causing severe problems. The Middle Ages darkened due,

at least from our modern point of view, to the consequences of these

crises, coupled with the image of the Middle Ages created by scholars in

the nineteenth century. Temporal distance makes the whole appear

simpler and more aestheticized than it actually was, and any picture of

the Middle Ages brings with it an ominous element - anti-Semitism, as

hatred of Jews is now being called. The ultimate consequences of this

development are to be found in the unfortunate 1930s and 1940s. With the

image of these years in mind, it is actually possible to talk about a

contemporary, dark "Middle Ages" - those allegedly responsible are not

inhabitants of the real Middle Ages, but representatives of the present.

Seen from this perspective, one could say that since the 1940s Europe

has been trying gradually to re-find the twentieth, that is to say it's

own, century.

To return to the real Middle Ages, Mathieu le Juif

converted to Christianity and experienced his new isolationary existence

as a catastrophe, whilst Süskind of Trimberg remained committed to

Judaism and felt himself to be equally isolated as a result of the

expulsion and homelessness imposed on him by a judaeophobic environment.

The

Jews of Moorish Spain, known as Sephardim, who formed the other great

Jewish society, were also not safe from discrimination and persecution

by their Islamic rulers. However, they enjoyed comparative freedom: as

non-Christians they did not present a direct challenge to the regime;

they did not represent Christian States or kings with missionary

ambitions. Moreover, well-versed in other languages, Sephardic Jews

mediated between classical antiquity and a young, Islamic society

thirsting for knowledge. Whilst Ashkenazim (i.e. German Jews) were

excluded from guilds and societies and barred from taking public office,

Sephardim held positions in universities and even in the civil service,

thereby becoming the first Jewish "aristocrats" of modern times. But

there were both Ashkenazic and Sephardic poets and thinkers, despite the

sometimes oppressive-conditions for Jews in Christian Central Europe.

Poets and thinkers can be found amongst these speakers of Middle High

German, Jewish German and French as long as the illusion remains, which

is to say, until they were consumed by the fires of persecution. Both

Sephardim and Ashkenazim were strongly influenced by their immediate

environment and in this respect are comparable with any other minority.

They used local poetic forms and adopted languages and melodies, thereby

giving Jewishness every different character in different parts of

Europe. But a common underlying basis, and indeed that which links

Central Europe Jewry with that of the Meïterranean and the Middle East,

is provided by the Torah (the five Books of Moses), the Talmud (a very

rich literature of responsa), and a language, which next to Ladino,

Jewish German and Jewish Arabic serves as a universal language: Hebrew.

The language of the Torah.

For the past two hundred years the

study of Hebrew for the pupils of Cheder, for example, has begun in a

highly sensual manner: the teacher drips honey on each letter, so that

the language to be learnt becomes at the same time a matter of physical

importance and, most certainly, a matter of the heart. Furthermore, each

individual letter and the language itself in general, is dealt with in

every conceivable way. Each word and grammatical function is examined

and defined from every possible angle. So, being accompanied by a

benediction and therefore receiving linguistic explication, each act is

fully explored and defined in detail - a blind man could follow the

events.

For the past two hundred years the

study of Hebrew for the pupils of Cheder, for example, has begun in a

highly sensual manner: the teacher drips honey on each letter, so that

the language to be learnt becomes at the same time a matter of physical

importance and, most certainly, a matter of the heart. Furthermore, each

individual letter and the language itself in general, is dealt with in

every conceivable way. Each word and grammatical function is examined

and defined from every possible angle. So, being accompanied by a

benediction and therefore receiving linguistic explication, each act is

fully explored and defined in detail - a blind man could follow the

events.

The "sensuality" of the letters explains their position

in relation to music. Unlike the Christian mass, a synagogue service has

never developed into a musical genre. This may largely be due to the

enormous difficulties the Jews experienced in trying to integrate with

society, but was possibly also a consequence of their own anxious

isolation. Even though language is always a translation, a translation

of an inner event, it appears to be more objective and unambiguous than

music. (Yet, music plays a very important role in every society, not

only when reciting a text in front of a large group of people. The

singing voice carries the text further than the speaking voice would

allow.) However, in the long term, this may also have been influenced by

the views of the interpreters of Judaism, bearing in mind that

discussions of the role of music in Jewish society permeate the Middle

Ages. On the one hand, the rabbinical view was that music distracts from

the essential, by giving pleasure whilst listening and in particular,

by its capacity to arouse excessive human passions. On the other hand,

the cabalists argued that music is an essential part of the text, able

to provide meaning beyond words.

For the Hasidei Aschkenas,

German mystics of the 13th century, a melody was a prerequisite to any

expression of the love of God and the joy of the commandments. Music for

them provided the basis of the Kavvanah (concentration), serving to

deepen the concentration of the cantor in particular. For that reason

Yehuda He-Chassid, in the thirteenth century book Safer Hassidim, says

that one should select the melody for a text according to one's own

preferences. Most of the songs on this record were created according to

this principle.

The only authentic musical material belongs to

the songs of Obadiah. These pieces, notated in neumes, lay undiscovered

until 1763, when they were found in the Cairo Geniza, an outstanding

source of knowledge of the life of medieval European Jewry. As a Jewish

convert, Obadja illustrates the fact that there were indeed Christians

converting to Judaism, if only up until the time of the Crusades and

great plagues. There are no indications of rhythm or dynamic in the

source, so the text itself and it's speech rhythms are used as

guidelines for this recording. For the rest of the songs, the melodies

reflect the preference of the ensemble and were, whenever possible,

chosen for their contemporaneity with and topographical nearness to the

texts. In addition, when using popular songs, the theme of the original

text was also taken into account. For example, the song "Libi

be'Misrakh" is a lamentation of the poet who suffers because he is far

away from Jerusalem. The melody to this text is taken from the song "Ir

me quiero a Yerushalayim". The poems are linked by the yearning for

Jerusalem. The technique applied here is called contrafactum and is far

from uncommon. Indeed, examples of contrafactum are found throughout the

history of music and there are many reasons for it's use. A popular

melody is often utilised for new poetic creation, enabling a new song to

be learnt more quickly - a technique that is of particular interest to

the clergy when, for example, a text should gain speedy and wide

acceptance.

The care taken with the interpretation and the

efforts to create an awareness of human existence through language are

above all directed towards one single place, towards Jerusalem.

Jerusalem is the former city of the Temple, where the Schekhina, God's

presence on earth, dwells; the place from which the Jews were exiled by

the Romans in 70 CE, following the destruction of their centre, the

Temple. Since that time, all hope has been invested in the Messiah, who

will come and rebuild the temple. This hope takes on very different

appearances over the centuries, a major factor being the increasing

temporal distance from the traumatic events.

This longing has a

name; how it manifests itself is another matter. In the "Iggeret Teman",

a letter to the Jews of Yemen (written whilst they were in a state of

confusion over one of the many messianic appearances), Maimonides wrote

that people should no longer orientate themselves towards a return to

Jerusalem. This letter was certainly intended as a sedative, meant to

prevent both the disintegration of Jewish society and an uprising in the

Yemenite community. However, it illustrates the rejection of the idea

of a concrete return to Jerusalem in favour of the city and temple

becoming a symbol of greatness, which can be called hope.

This

unquieted but alive hope releases great strength. A poem like the one

already mentioned, "Libi be'Misrakh", is written to expresses the

anxiety, grief and despair of the poet who is far from Jerusalem. It

emphasises the nature of the relationship, acknowledging the importance

of the individual and the object of his desire, but stressing the

relationship or exchange between the two. Jerusalem can thus be a

direction to which the Jew turns in prayer — an act which further refers

to God. In this way, the relationship is like the one between the lover

and his beloved in the Song of Songs.

Esther Kontarsky

Translation: Jessica Marshall