medieval.org

Almaviva 0123

abril de 1996

Alepo

موسيقى أندلسية • La música de al-Andalus

موشـّحات • La muwaššaḥa

التراث • al-turāth

waṣlah de maqām ḥijāz

medieval.org

Almaviva 0123

abril de 1996

Alepo

موسيقى أندلسية • La

música de al-Andalus

موشـّحات • La

muwaššaḥa

التراث • al-turāth

waṣlah de maqām ḥijāz

The andalusi

muwashshaḥ

01 - samāºi [7:07]

02 - muwashshaḥa. yā ghuṣayna-l-bāni [3:18]

03 - muwashshaḥa. mā-htiyālī' [5:38]

04 - muwashshaḥa. hajarnī ḥabībī [1:40]

05 - muwashshaḥa. yā fātina-l-ghuzlān [4:33]

06 - muwashshaḥa. ºunqu-l-malīḥ [3:45]

07 - dūlāb [2:50]

08 - taqsīm [1:49]

09 - layālī. yā laylī yā ºaynī [5:25]

10 - qaṣīdah [8:26]

11 - qad. yā māyilah ºalā-l-ghuṣūn ºaynī [6:09]

12 - mawwāl [4:40]

13 - qad. fūq an-nakhil [4:49]

14 - qad. al-bulbul nāghā ºaghuṣni-l-fill [4:50]

15 - qad. qadduka-l-mayyās yā ºumrī [6:58]

16 - qad. bīnī w-bīnak ḥārū-l-ºawāzil [2:55]

AL-TURATH ENSEMBLE

dirección: Muhammad Hamadiyih / Muḥammad Ḥamādiyih

solistas y coristas: Mahmūd Fāris, Rabīº ash-Shahir, Ahmad

Kabbari, ºAli Muhsin

coristas: Mahmud Hamadiyih, Muhammad Hamadiyih

kamān (violín): ºAbd al-Basit Bakkar, Rafwan

ºAbd al-Qadir, Khalid Budaqah

ºūd (laúd): ºAbd ar-Rahim ºAjin

qānūn: Yusif Salim

riqq (tambor): Jamal Shamiyih

darabukkah (tambor): ºAbd al-Qadir Shamiyih

THE ANDALUSI WAṢLAH

OF ALEPPO, SYRIA

waṣlah

A waṣlah is the performance of up to eight muwashshaḥāt

(plural of muwashshaḥa) in succession together with an

instrumental introduction. Common to all sections of such a waṣlah

cycle is the principle maqām row, whereby the combination of

pieces can comprise the works of several poets and composers. The

muwashshaḥ composition played at the beginning of a cycle may have a

longer wazn than the muwashshaḥāt that follow. A total of 22

waṣlāt (plural of waṣlah) are known in Aleppo, each of them named

according to the maqām row to which it belongs (for exmple, waṣlah of

maqām rāst, waṣlah of maqām ḥijāz, waṣlah of maqām sīkāh).

maqām

The term maqām designates a modal framework in the music of the Arabs.

It denotes not just the intervallic distances between tones of

specifics order, but rather the mood created throught realization and

presentation of the modal framework based on such on order of

intervallic distances, which themselves make up what is called the

maqām row or the maqām mode. From a historical point of view, the term

maqām became a common property of Arabic-Islamic musical scholars in

the fourtenth century.

The maqām represents a unique improvisatory process in the art music of

the Arabs and in the art music of a large part of the world

encompassing the cultures of North Africa, West and Central Asia. The

structure of a maqām depends upon the extent upon to which the tonal

and temporal factors exhibit a fixed or free organization. The

tonal-spatial component is organized, molded and emphasized to such a

degree that it represents the essential and decisive factor in the

maqām, whereas the temporal-rhythmic aspect in this music is not

subject to a definite form of organization. In this very circumtance

lies the most essential feature of the maqām phenomenon, that is, a

free organization of the rhythmic-temporal and an obligatory and fixed

organization of the tonal spatial aspect. The maqām is thus not subject

to rules of organization where the temporal parameter is concerned,

that is, it has neither a regularly recurring and stablished bar scheme

nor an unchanging tactus. The rhythm characterizes the performer's

style and is dependent on his manner and technique of playing or

singing but is never characteristic of the maqām as such. The singular

feature of this form is one which is not built upon motifs, their

elaboration, variation and development, but throught a number of

melodic passages of different lengths that realize one or more

tone-levels in space and thus establish the various phases in the

development of the maqām. The maqām is based upon a systematic

realization of tone-levels which gradually move upwards from the lower

to the higher registers until the climax is reached, at which point the

form is completed. The realization of a truly convincing and original

maqām requires a creative faculty like that of a composer of genius.

Nevertheless, this phenomenon can only in part be considered as a

composed form because no maqām can be identical with any other: each

time it is recreated as a new composition. The compositional factor

shows itself on the predetermined tonal-spatial organization of the

fixed number of tone-levels without repetitions, while the

improvisational aspects freely unfolds in the rhythmic-temporal layout.

The interplay of composition and improvisation is one of the most

distinctive features of the maqām-phenomenon.

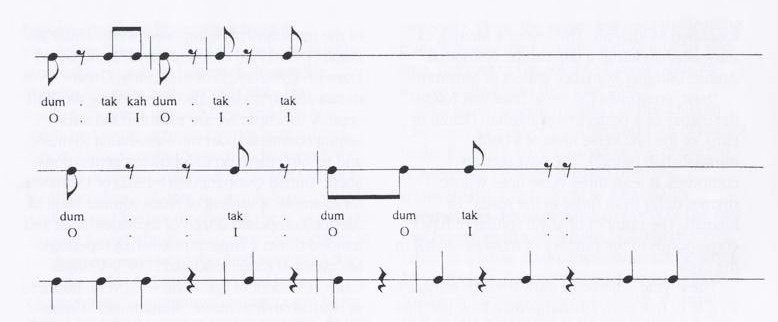

wazn

Genres with a fixed rhythmic-temporal organization have clear, compact,

regularly recurring measures which cause an organized, easily

recognizable segmentation of time. The muwashshaḥ belongs to this

genre. On the other hand, genres with a free rhythmic-temporal

organization have a rhythmic-temporal structure without regularly

recurring measures and motives and without displaying a fixed meter

(pulse). The taqsīm belongs to this genre. Nevertheless, the rhythmic

pattern in Arabian music is called wazn, literally "measure". Such

patterns are also known by the names uṣūl, mizān y ḍarb.

The Arabian wazn repertoire is comprised of approximately 100 cycles.

A few examples of Arabian awzān (plural of wazn) rhythmic patterns:

The term muwashshaḥ is applied to an autonomous vocal art music genre

of the Arabs that is textually based on the poetic form of the same

name. In his book dār aṭ-ṭirāz, the autor Ibn Sanāº al

Mulk (1155-1211) defines the muwashshaḥ as a poetry of a special meter

(syllabic groups) kalām manẓūm ºala wazn makhṣūṣ. The word

muwashshaḥ means precisely adorned with and is derived from the

expression wishāḥ, which denotes a woman's decorated scarf with

pearls and jewels. The poetic form of a muwashshaḥ incorporates a

certain number of verse lines grouped into two categories: maṭlaº

or madhhab and bayt.

maṭlaº, or madhhab, comprises at least two verse lines,

whose end rhymes may be similar (aa) or dissimilar (ab). A muwashshaḥ

is called kāmil or ṭām, that is, perfect or complete,

when it comprises a maṭlaº; otherwise it is labelled aqraº,

that is, bald. However, the first muwashshaḥ in a cycle is always

complete, while next muwashshaḥ can be bald. A ideal cycle comprises

five muwashshaḥāt, though it should be noted that the last muwashshaḥ

is identified as kharjah. The text of a kharjah, a muwashshaḥ

kāmil or ṭām, can be colloquial Arabic, bilingual Romance dialect or

Mozarabic.

bayt comprises the verse lines that follow the maṭlaº of a

perfect muwashshaḥ (kāmil or ṭām), or the first verse lines of a bald

muwashshaḥ (aqraº). The bayt section comprises at least three

verse lines whose rhymes differ from those in the maṭlaº or

kharjah. The number of abyāt (plural of bayt) corresponds to the number

of muwashshaḥāt in the cycle.

This poetic form is also known by the name zajal. Zajal poems,

though, may be composed in colloquial Arabic. Muwashshaḥ poets avail

themselves of classical Arabic.

A specific muwashshaḥ can be more precisely identified by naming the

first line of the poem, the principle maqām row, the accompanying

rhythmic pattern as well as the names of the poet and composer. For

most of the well known traditional muwashshaḥāt, however, data

pertaining to the person of the poet and composer is lacking. In place

of this information, one ususlly encounters the reference qadīm

("old").

Regarded as the most productive and original of the muwashshaḥ

composers were ºUmar al-Batsh (1885-1950) of Aleppo and Sheik

Sayyid Darwish (1892-1923) of Alejandría. Great muwashshaḥ

masters also lived during the 19th century to whom we are indebted

today for setting countless older muwashshaḥāt to music and passing

them on to following generations. Sheik Ahmad Qabbāni (1841-1902) of

Damascus, for example, a student of Sheik Aḥmad ºAqil of Aleppo,

composed dozen of muwashshaḥāt and handed down a large muwashshaḥ

repertoire. Muḥammad Kāmil al-Khulaci (1879-1938) of Cairo, a student

of Qabbāni, set several hundred muwashshaḥāt to music. Muḥammad

ºUtmān (1855-1900) of Cairo, student of the great qanun master

Qustāndi Mansi, created more than 150 muwashshaḥāt. Among-the important

muwashshaḥ researchers and collectors to be mentioned are in particular

the Lebanese Salim Hīlu, the late Sheikh ºAli Darwīsh and his son

Nadīm of Aleppo, as well as Ibraḥīm Shafiq of Cairo.

In the 9th century, Ziryāb, the great singer at the court of Harūn

ar-Rashīd, left Bagdad after a quarrel with his teacher, Isḥāq

al-Mawṣilī and emigrated to Islamic Spain, i.e., Al-Andalus. He founded

a music school in Cordoba where he carried on the musical tradition of

the early Arabian Classical School of Baghdad - not, however, without

liberating it from its classicism. Ziryab's school in Cordoba quickly

attained far-reaching influence. In Seville, Toledo, Valencia and

Granada also, his teachings were a guiding light and newly stablished

music schools everywhere turned Ziryab's innovations to practice.

However, the muwashshaḥ was invented in the 9th Century by Muqaddam

al-Qabrí in Islamic Spain, i.e., Al-Andalus, and further

developed there as a poetic musical form before it also came

appreciated in the esastem regions of the Arabian world, the Mashriq

states of Egypt, Syria and Iraq. Characteristic of the muwashshaḥ poem

is that althought it is composed in classical Arabic, it is not based

on any of the 16 classical meters of Arabian poetry. Otherwise also,

the muwashshaḥ poem does not exhibit any fixed sequence of stress and

arsis, but rather groups these to conform to a specific musical

rhythmic pattern (wazn). Thus, linguistic and musical rhythm in the

muwashshaḥ are inseparably linked to one another. The musical form ABA

is analogous to the poetic form AAbbbAA or ABABcccABAB. The term

muwashshaḥ, however, not only designates the poem, but also the musical

section in which the poem is sung. In each muwashshaḥ the tones and

tonal areas characteristic of the maqām are developed musically. Here,

the singer assumes the leading role. Whereas the instrumentalists

indeed also sing, the part of the soloist often appears an octave

higher than the choir part.

The muwashshaḥ tradition of the Arabian East - from Aleppo of the 18th

and 19th centuries to the Egyptian muwashshaḥ of the present - is,

however, to be distinguished from the muwashshaḥ poetic form of

Al-Andalus inasmuch as the muwashshaḥ poets of the East feel bound to

the strict rules of Arabian meter, while in Islamic Spain, these rules

are ignored. Nevertheless, the muwashshaḥ is still regarded today, in

Mashriq also, as andalusí, something that in fact also holds

completely true for the musical performance form.

In a muwashshaḥ ensemble, the instrumentalists often also make up the

choir. The part of the solo singer consists usually of only a few of

the lines presented. The instruments performing are the plucked short

necked lute (ºūd), the violin (kamanjah), the

plucked box zither (qanūn), the goblet drum (darabukkah)

and the tambourine (daff). In Aleppo, muwashshaḥāt were composed

on several maqām rows and presenting up to three awzān. Moreover, in

the bayt section of a muwashshaḥ, it was also possible to modulate to

neighboring maqāmāt.